I think that it has to do with the difference between the idea of “archiving” versus the idea of “reproduction,” the translation that has to occur from one media to another, and the object that each ultimately produces. Both a physical reproduction and a digital archive create an image of the book, but how that image functions is different in each case. The physical reproduction creates an image-in-multiple, a surrogate meant to stand in for an “original.” The reproduction is explosive, outward-reaching. The digital archive creates an image-of-multiplicity, a document of the object (book) in question. The archive is implosive, inward-drawing, and allows for the original multiplicity of the object-in-question to be maintained.

The Drownable Species can provide us with a specific example. That book is a printed work, made in multiple, but the edition is variable—every copy is different. There is no “original” or even a “match” or BAT that each copy tries to emulate. The difference in the repetition of the individual copies was part of the process of printing, created by pouring and brushing water and ink wash onto still-wet inkjet printed images. So, if one was to make a physical reproduction of the book, how does one choose which copy to reproduce? The “best” one? The “most average” one? And, is it possible that if there was a more accessible reproduction (more numerous, more affordable) that only replicated a single copy, that that single reproduction (the

image-in-multiple, the

surrogate) could supplant the variable edition and create the false idea that there is an “original” or a “best” copy? Would the reproduction actually create an

aura for an original that was never supposed to exist in the first place?

The other, more mundane problems that would come along with a physical reproduction are the problems that come with every book—how to pay for it and how to get it out in the world. Ordinarily those are good challenges, but they are less enticing to take on when the book being produced is just a shadow-copy of one already made.

How would a digitally archived version of

The Drownable Species be different? First of all, the digital version doesn’t have the same problems of distribution and expense to produce. It’s more about time than anything else. And, because of that efficiency, other opportunities are allowed. When

The Drownable Species is finally archived (& it’s in the works) there will actually be three different copies posted—the multiplicity of the original will be built-in, and readers will be able to look at all three copies and see how they are different. (The idea of which came from

The William Blake Archive, where one can compare the same page from all of the copies of one of Blake’s books.)

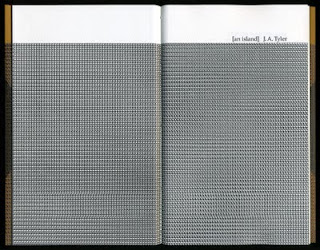

But what about a unique book? How can the identity of the original be embedded into the digital version? The image files for the digital version can be built in a certain way that alters their “transparency”—they can be constructed to show their construction. More on that soon.