skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The hand-mechanical is a deliberate manipulation of the codes and conventions of artistic practice.The first and most obvious of those codes/conventions put into play by the hand-mechanical is the (limited) edition. (From here through the rest of this post, the term “edition” will be used to refer to a “limited edition,” but specification will be used when necessary.) Hand-mechanical processes can be employed to produce an artwork in multiple, but can they be used to make a proper edition?What is a “proper” edition anyway? When a work is done in an edition (usually a print, book, or photograph, sometimes a sculpture, sometimes something else, and it’s that something else we’re interested in) the original artwork is made in multiple. There is not one original and then a number of copies, there is no single, stable source—the editioned artwork is multiple, the multitude, plenitude, the network, the rhizome, from its very beginning. The matrix that is needed to make an editioned artwork (the printing plate, the photographic negative, the mold, and yes, the digital file) is not a part of the finished piece—it is part of the process, no more and no less a “source” of the artwork than a pencil is the “source” of a drawing. A “proper” edition[Definition break (it’s best to proceed slowly): “proper” here means “as traditionally defined and realized.”]

A “proper” edition[Definition break (it’s best to proceed slowly): “proper” here means “as traditionally defined and realized.”] A “proper” edition is almost always a limited edition. The original edition is produced once, and that’s it, no more. The matrix is theoretically destroyed (“canceling the plate”) to insure that no unauthorized copies [“copies?”] can be made. Every piece in the edition is supposed to look exactly the same. Any copies that are noticeably different from the others are excluded. The amount of variation tolerated in an edition varies from artist to artist, from piece to piece, from context to context. There is no “perfect” edition—every edition contains the very thing (variation, difference) that cancels its mode of being, that activates its mode of becoming.

A “proper” edition is almost always a limited edition. The original edition is produced once, and that’s it, no more. The matrix is theoretically destroyed (“canceling the plate”) to insure that no unauthorized copies [“copies?”] can be made. Every piece in the edition is supposed to look exactly the same. Any copies that are noticeably different from the others are excluded. The amount of variation tolerated in an edition varies from artist to artist, from piece to piece, from context to context. There is no “perfect” edition—every edition contains the very thing (variation, difference) that cancels its mode of being, that activates its mode of becoming. We could describe the limited edition with the paradoxical term singly multiple: it is multiple, but that multiplicity is contained within a single iteration. The unlimited edition is, in theory, infinitely multiple: in order to be unlimited, the edition must be produced in multiple iterations (first printing, second printing, third printing, and so on) or be in constant production, on a machine set to run and produce forever.[Idea: limit an edition not by number of copies, but by amount of time spent in production. The edition is x number of copies produced in y units of time. “This is an edition of three days (that happens to include 304 copies).” Should one exclude variant copies as usual, or should one include all copies, even the really messed up ones? Does the use of the time boundary require the shattering of the edition’s consistency?]

We could describe the limited edition with the paradoxical term singly multiple: it is multiple, but that multiplicity is contained within a single iteration. The unlimited edition is, in theory, infinitely multiple: in order to be unlimited, the edition must be produced in multiple iterations (first printing, second printing, third printing, and so on) or be in constant production, on a machine set to run and produce forever.[Idea: limit an edition not by number of copies, but by amount of time spent in production. The edition is x number of copies produced in y units of time. “This is an edition of three days (that happens to include 304 copies).” Should one exclude variant copies as usual, or should one include all copies, even the really messed up ones? Does the use of the time boundary require the shattering of the edition’s consistency?]

An artwork could be made in an edition that is somewhere between those two poles: doubly multiple, triply multiple, etc. But is an unlimited edition masquerading as limited to drive up value, or a limited edition designed to exceed its own limits? Unique artworks exist in a restricted economy in its most restricted sense. Uniqueness is the ultimate scarcity.Limited edition artworks, depending on the size of the edition and the mode(s) in which that edition is deployed in the world, can function in either a restricted economy or a general economy (an economy of excess, plenitude). “Proper” editions exist in a restricted economy. An “improper” edition might be limited but can be deployed in such a way as to disregard its own scarcity—given away or sold cheaply.The unlimited edition is a theoretical practice—an edition is always limited, because we are finite beings in a finite world.

Unique artworks exist in a restricted economy in its most restricted sense. Uniqueness is the ultimate scarcity.Limited edition artworks, depending on the size of the edition and the mode(s) in which that edition is deployed in the world, can function in either a restricted economy or a general economy (an economy of excess, plenitude). “Proper” editions exist in a restricted economy. An “improper” edition might be limited but can be deployed in such a way as to disregard its own scarcity—given away or sold cheaply.The unlimited edition is a theoretical practice—an edition is always limited, because we are finite beings in a finite world.

[As of this writing, as of this reading, here, in this soft, snowy morning in Colorado, my finite amount of time is scraping against the ragged edges of this post. It really is a mess, but we will start here, with this heap, already spilling over, and see what we can do.]

[As of this writing, as of this reading, here, in this soft, snowy morning in Colorado, my finite amount of time is scraping against the ragged edges of this post. It really is a mess, but we will start here, with this heap, already spilling over, and see what we can do.]

This seems appropriate to the current line of posts, and to the NewLights Press in general:Impractical Labor in the Service of the Speculative ArtsFrom the site:Impractical Labor is a protest against contemporary industrial practices and values. Instead it favors independent workshop production by antiquated means and in relatively limited quantities. Economy of scale goes out the window, as does the myth that time must equal money. Impractical Labor seeks to restore the relationship between a maker and her tools; a maker and her time; a maker and what she makes. The process is the end, not the product. Impractical Labor is idealized labor: the labor of love.I love the tagline: "As many hours as it takes!!!"

From 5aThe hand-mechanical is, at least in my formulation of it, “monkish business.” These processes are quiet, disciplined, meditative, and are, to a large degree, hidden. Hidden not for secrecy, but for humility, to keep the process a process willingly undertaken, and to avoid the pitfall, the temptation, of performing the process. The process must, at all costs, be kept from becoming an image, from passing into a stable, transferable, and consumable representation. The process must repetitively dismantle and destroy any image of itself. The process must be thoroughly infused into the facts and factitiousness of the object as an object. The process must be a thing done, in time, a task completed and here, here, in the object that is in the reader’s hands.& into 5b, which will pull its predecessor to piecesThere are a few different things going on, a few different ideas circulating, in the paragraph above. We will get at them through the question of authenticity: “to avoid the pitfall, the temptation, of performing the process.” What is “performing” the process? I would define it as using a particular working method because of the meaning of that method, and that meaning may be more than, or just as important as, the actual results. A method performed is a method deployed because of its ability to act as a signifier in and of itself. The performer acts with a large degree of self-consciousness. The conventions of the method are taken up, examined, and are either left intact, or they are disturbed, tweaked, displaced, reworked. What is the opposite of “performing” a process? A process not performed is a process simply done. It exists as an event, in time, mute (yet always legible, like everything, to the desire to read), in the same way that the sun rises, the wind blows. The process done is engaged with by the artist as a fact, conventionless, its meaning and role so stable that there is, essentially, no meaning. The thing done is a thing real, of this world. The thing done is an authentic act in a simulated discourse.

What is the opposite of “performing” a process? A process not performed is a process simply done. It exists as an event, in time, mute (yet always legible, like everything, to the desire to read), in the same way that the sun rises, the wind blows. The process done is engaged with by the artist as a fact, conventionless, its meaning and role so stable that there is, essentially, no meaning. The thing done is a thing real, of this world. The thing done is an authentic act in a simulated discourse. [Here, here, is where the reversal, the folding, the doubling, of terms begins. It is never a question of one or the other.]

[Here, here, is where the reversal, the folding, the doubling, of terms begins. It is never a question of one or the other.] The idea of authenticity is an idea that is politically hard to let go of. If the world is shaped by economic flows and the spectacles of corporate power, then “authenticity,” of an act, of an experience, or of a person, is one of the few anchors that we have. And authenticity is important, necessary even. But authenticity is not the same thing as innocence. Authenticity comes from a deep and sustained engagement with an idea, to the point where the idea becomes inseparable from the one who struggles with it. Every role, every medium, every sign, every thing, every meaning is, authentically and at its root, unstable and multiple. The “performer” accepts this instability and manipulates the codes and conventions of the role, to see what new material it can yield. The one who simply “does” believes thoroughly in the stable meaning of their role, of their method, or wants to believe thoroughly in the stable meaning of their role, of their method.

The idea of authenticity is an idea that is politically hard to let go of. If the world is shaped by economic flows and the spectacles of corporate power, then “authenticity,” of an act, of an experience, or of a person, is one of the few anchors that we have. And authenticity is important, necessary even. But authenticity is not the same thing as innocence. Authenticity comes from a deep and sustained engagement with an idea, to the point where the idea becomes inseparable from the one who struggles with it. Every role, every medium, every sign, every thing, every meaning is, authentically and at its root, unstable and multiple. The “performer” accepts this instability and manipulates the codes and conventions of the role, to see what new material it can yield. The one who simply “does” believes thoroughly in the stable meaning of their role, of their method, or wants to believe thoroughly in the stable meaning of their role, of their method.

The stability of signification is one of the oldest illusions. Feigned innocence will be the death of us all. And now the text gives way to a new formulation:The hand-mechanical is a deliberate manipulation of the codes and conventions of artistic practice.The photograph used in this post, in its singular form, is: Art Kane, Andy Warhol as Golden Boy, c. 1960, color photograph.

The stability of signification is one of the oldest illusions. Feigned innocence will be the death of us all. And now the text gives way to a new formulation:The hand-mechanical is a deliberate manipulation of the codes and conventions of artistic practice.The photograph used in this post, in its singular form, is: Art Kane, Andy Warhol as Golden Boy, c. 1960, color photograph.

Yesterday I paid a visit to Special Collections at the Tutt Library here at Colorado College. We have a great little collection here, and it’s always fun and interesting to go up there and look at and page through things. Somehow during yesterday’s discussion the above photograph was produced from the archives. It is from c. 1920, and it shows Archer Butler Hulbert sitting in the Colorado Room in Coburn Library at Colorado College.Getting closer everyday.

Yesterday I paid a visit to Special Collections at the Tutt Library here at Colorado College. We have a great little collection here, and it’s always fun and interesting to go up there and look at and page through things. Somehow during yesterday’s discussion the above photograph was produced from the archives. It is from c. 1920, and it shows Archer Butler Hulbert sitting in the Colorado Room in Coburn Library at Colorado College.Getting closer everyday.

The hand-mechanical is anti-spectacular and anti-heroic.A little over a month ago now Darren Wershler came to Colorado College as a visiting lecturer for the Press. (His visit was what led me to reading his book on typewriting and typewriters, The Iron Whim, mentioned in a previous “Machined” post.) Before his visit we had done a broadside with him, a broadside that relied on delamination, so the hand-mechanical was very much on my mind during his visit. On the second day of his visit, Darren did a workshop/discussion/lecture with a group of students (and a few faculty & staff), and in that discussion he mentioned Kenneth Goldsmith and his piece Day, where he re-produced a particular issue of The New York Times.I had always been under the impression that Goldsmith had physically retyped the newspaper. But according to Darren (a friend of Goldsmith’s) he did not. Goldsmith began by retyping the newspaper, and after doing that for a while, he decided to scan and OCR (optical character recognition, to convert the scanned image to malleable text) them. When Darren first disclosed that fact, I was, I admit, shocked. The mythology of that piece, and thus of Goldsmith’s work in general, was shattered. This was particularly disappointing because I had been thinking, for a while now, at least since the writing of the first iteration of The New Manifesto..., of Goldsmith’s “uncreative writing” practice as a writerly example/precedent for the hand-mechanical. This massive, interior deflation of mine occurred in about one second. Then the whole thing changed completely, because Darren when on to say something more, telling how Goldsmith thought that the act of typing the newspaper was too heroic, that it was the sort of thing that he could do in a gallery window, that the typing became a kind of performance that focused on his (heroic/nostalgic because of the typewriter) labor. But if he scanned them, then what he was doing wasn’t special, wasn’t heroic. He was replicating the way that written documents are converted to digital text every day, by the assembly line workers of the information economy.One could make the argument that Goldsmith was not concerned about the “heroism” of his typing, that what he was concerned with was the amount of time-energy that it was going to take, and that he switched methods because he got lazy. One could make that argument. But we’re not interested in that argument, because the idea of the implied heroism of a process, or of its display, has helped me to articulate what I think is an important aspect of the hand-mechanical: The hand-mechanical is anti-spectacular and anti-heroic.(I did retype that sentence, instead of copying/pasting, but you would never know, nor should you ever believe me, here, here, in the realm of seamless replication.)The hand-mechanical is, at least in my formulation of it, “monkish business.” These processes are quiet, disciplined, meditative, and are, to a large degree, hidden. Hidden not for secrecy, but for humility, to keep the process a process willingly undertaken, and to avoid the pitfall, the temptation, of performing the process. The process must, at all costs, be kept from becoming an image, from passing into a stable, transferable, and consumable representation. The process must repetitively dismantle and destroy any image of itself. The process must be thoroughly infused into the facts and factitiousness of the object as an object. The process must be a thing done, in time, a task completed and here, here, in the object that is in the reader’s hands.

The hand-mechanical is anti-spectacular and anti-heroic.(I did retype that sentence, instead of copying/pasting, but you would never know, nor should you ever believe me, here, here, in the realm of seamless replication.)The hand-mechanical is, at least in my formulation of it, “monkish business.” These processes are quiet, disciplined, meditative, and are, to a large degree, hidden. Hidden not for secrecy, but for humility, to keep the process a process willingly undertaken, and to avoid the pitfall, the temptation, of performing the process. The process must, at all costs, be kept from becoming an image, from passing into a stable, transferable, and consumable representation. The process must repetitively dismantle and destroy any image of itself. The process must be thoroughly infused into the facts and factitiousness of the object as an object. The process must be a thing done, in time, a task completed and here, here, in the object that is in the reader’s hands. This is getting difficult, now, because the process must also be an image of itself unfolding, an image that is transferable to the reader, so that they can, potentially, enact it themselves, or at least understand it, or at least destroy it, themselves.

This is getting difficult, now, because the process must also be an image of itself unfolding, an image that is transferable to the reader, so that they can, potentially, enact it themselves, or at least understand it, or at least destroy it, themselves. So the image must exist. But its meaning must be precise. How is precision in meaning possible in a system with multiple inputs and outputs? How is exactness in meaning justifiable in a system that is claimed to be open? How can I, writing about this process, try to simultaneously dissolve and solidify my position of authority? Is that the game of the hand-mechanical?

So the image must exist. But its meaning must be precise. How is precision in meaning possible in a system with multiple inputs and outputs? How is exactness in meaning justifiable in a system that is claimed to be open? How can I, writing about this process, try to simultaneously dissolve and solidify my position of authority? Is that the game of the hand-mechanical?

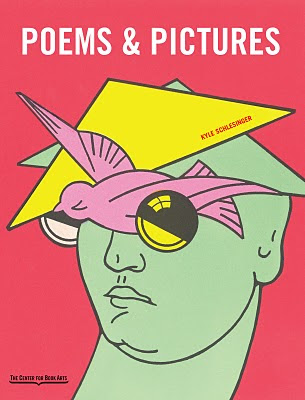

The catalog for the exhibition Poems & Pictures: A Renaissance in the Art of the Book: 1946-1981 is now available for purchase via Oak Knoll. The show was curated by Kyle Schlesinger, NewLights author, proprietor of Cuneiform Press and all-around fine human being. The catalog has tons of images and some great descriptions of the various presses represented in the show. I am honored to be a part of it.

The catalog for the exhibition Poems & Pictures: A Renaissance in the Art of the Book: 1946-1981 is now available for purchase via Oak Knoll. The show was curated by Kyle Schlesinger, NewLights author, proprietor of Cuneiform Press and all-around fine human being. The catalog has tons of images and some great descriptions of the various presses represented in the show. I am honored to be a part of it.

The hand-mechanical is not (necessarily) obsessive. Describing a hand-mechanical practice or approach to a piece as “obsessive” means, of course, “obsessive compulsive,” means, of course, that the artist is a little crazy. And if the artist is “crazy” then their work (and they themselves) are some sort of aberration, a mistake, an anomaly, and while the hand-mechanical process can be enjoyed by the viewer, it is not something that they can understand, because, as the product of a mind that is a little off, there is nothing, essentially, for the viewer to understand. The process becomes a kind of spectacle for the viewer to consume.The label of obsessive immediately denies the idea that the artist came to the choice of using a hand-mechanical approach comfortably and rationally, and that that approach, that process, is integral to the concept of the piece. (Brief aside. Concept: The overall arrangement of the entire idea for the piece. Concept contains form, content, modes of production, and modes of reception. Concept is the arranged relationship between those four things. Content: what the piece is about. Could be personal, political, spiritual, self-referential, theoretical, etc. Content is one piece of the concept. These terms are way too confused in day-to-day art discourse. (There’s a day-to-day art discourse?)) A hand-mechanical process can be used rationally, should be used rationally and logically, to examine artistic (and other kinds, “non-artistic”) labor. What are the internal qualities of a hand-mechanical process, and how do they affect the other internal qualities of the piece, such as form and content? How can the process of making affect the process of reception/distribution, and vice versa? Can an intensive process have external qualities? Does it have something to do with the world? What are the parameters that determine whether labor is artistic? What kind of labor and laborers are author-ized? What kinds of labor and laborers are not allowed to share in the act of creation? What kind of labor is agency in action, and which kind of labor is a denial of agency?An activity that is undertaken by an artist because they are “compelled” to do so by a mental disorder is an activity whose critical capacity can be easily dismissed. (To be clear: the sentence before this is being critical of a particular critical attitude, and is not a dismissal of the work of the mentally ill as “non-artistic.” The hand-mechanical could potentially be used as a means to unpack how and why the work of the mentally ill is valued differently than the work of “normal” artists.) And so the label of “obsessive” denies the hand-mechanical, and the artist who uses it, of their agency, when in fact a hand-mechanical approach often is a seriously considered, self-effacing, critical application of that agency to the idea of artistic labor.

Working Method“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.” “[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.” “[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.” “[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.” “[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

“[The] process of [the stripe paintings was] simple-minded…. But it was a lot more intense; just doing those things, painting those stripes one after another is quite enervating and numbing. It’s physically fairly exacting…I couldn’t keep it up. The physical concentration…it was just a different kind of way of being a different kind of process. But the process was everything then, as it is now.”

Quote from Frank Stella. Retyped from: Caroline A. Jones, Machine in the Studio: Constructing the Postwar American Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 128. The quote originally came from an interview with Stella that was conducted by Caroline A. Jones. The brackets were put in by Jones.

My first experience with a hand-mechanical piece/process occurred during the first semester of the last year of my undergraduate education. It was at the beginning of that school year, and I hadn’t figured out quite what to do book-wise, so I was experimenting with approaches to writing that could be thought of as visual art (I was at an art school, majoring in Painting, though I had given up actually painting after I made my first book at the end of my sophomore year. But painting returns, slowly, changed by the book, in the hand-mechanical).I had a typewriter, my mother’s from college. I’m not sure what brand it was, but it was manual, with an almost completely dead ribbon that I was not interested in changing. The typewriter had become, in a weird way, the symbol of the kind of work that I was interested in at that time, partly maybe because of the nostalgia for writing, but mostly because the machine stood between writing and printing. It was like the letterpress, but portable, easy, informal. The letters left definite impressions on the page, which I tried to utilize in some pieces. I drew with it mostly, doing my “real” writing on a computer. The typewriter became, for me, at that time, less about the product of writing (text) and more about the process of writing (typing).

My first experience with a hand-mechanical piece/process occurred during the first semester of the last year of my undergraduate education. It was at the beginning of that school year, and I hadn’t figured out quite what to do book-wise, so I was experimenting with approaches to writing that could be thought of as visual art (I was at an art school, majoring in Painting, though I had given up actually painting after I made my first book at the end of my sophomore year. But painting returns, slowly, changed by the book, in the hand-mechanical).I had a typewriter, my mother’s from college. I’m not sure what brand it was, but it was manual, with an almost completely dead ribbon that I was not interested in changing. The typewriter had become, in a weird way, the symbol of the kind of work that I was interested in at that time, partly maybe because of the nostalgia for writing, but mostly because the machine stood between writing and printing. It was like the letterpress, but portable, easy, informal. The letters left definite impressions on the page, which I tried to utilize in some pieces. I drew with it mostly, doing my “real” writing on a computer. The typewriter became, for me, at that time, less about the product of writing (text) and more about the process of writing (typing). And so a piece developed that at the time seemed isolated, removed from the bookwork/publishing I was doing, but now I see that in it were latent ideas about the conventions of art and writing, of printing particularly, and how those conventions could be manipulated to draw the viewer’s attention to them. I didn’t really understand it that way at that time—I simply had an idea that on an intuitive level, “worked.”The piece was this: I sat at the typewriter and typed the phrase “I am a good man.” over and over again, once per line, in a single column down the page. This was repeated for 100 pages. I don’t remember now if I allowed typos to remain or if I retyped the pages with mistakes. The paper was plain, white computer paper, probably from some large office supply store. The type itself, because of the old ribbon in the machine, was light and uneven, and the impression was visible, so the sheets were obviously written with a typewriter. I numbered and signed them, 1/100, 2/100, 3/100… just like an artist would sign and number a print. And it ended with an “alternative” distribution model—I stood in the senior painting studio hallway (during an open studio tour) holding the stack and gave one to each person who walked by, and said to them, as seriously as I could, “I am a good man.” I remained in that spot until I had given every sheet away.Thinking back, it’s the first piece I made where the process of making was the driver of the overall concept (not content) of the piece. And process was connected to that content (the obsessive, devotional act), to the form (the machine composition, the aesthetics of the letters), and to the reception/distribution (the act of distribution turns the private devotion to a public insistence, the thing done becomes a thing real-ized, author-ized). A book of dispersed pages, all insisting the same thing, all exactly the same, each one totally unique. Not painting, not drawing, not printmaking, not writing, not performance, not completely.

And so a piece developed that at the time seemed isolated, removed from the bookwork/publishing I was doing, but now I see that in it were latent ideas about the conventions of art and writing, of printing particularly, and how those conventions could be manipulated to draw the viewer’s attention to them. I didn’t really understand it that way at that time—I simply had an idea that on an intuitive level, “worked.”The piece was this: I sat at the typewriter and typed the phrase “I am a good man.” over and over again, once per line, in a single column down the page. This was repeated for 100 pages. I don’t remember now if I allowed typos to remain or if I retyped the pages with mistakes. The paper was plain, white computer paper, probably from some large office supply store. The type itself, because of the old ribbon in the machine, was light and uneven, and the impression was visible, so the sheets were obviously written with a typewriter. I numbered and signed them, 1/100, 2/100, 3/100… just like an artist would sign and number a print. And it ended with an “alternative” distribution model—I stood in the senior painting studio hallway (during an open studio tour) holding the stack and gave one to each person who walked by, and said to them, as seriously as I could, “I am a good man.” I remained in that spot until I had given every sheet away.Thinking back, it’s the first piece I made where the process of making was the driver of the overall concept (not content) of the piece. And process was connected to that content (the obsessive, devotional act), to the form (the machine composition, the aesthetics of the letters), and to the reception/distribution (the act of distribution turns the private devotion to a public insistence, the thing done becomes a thing real-ized, author-ized). A book of dispersed pages, all insisting the same thing, all exactly the same, each one totally unique. Not painting, not drawing, not printmaking, not writing, not performance, not completely. Once Buzz Spector and I were talking about concrete poetry, and he put forth the idea that concrete poetry had ended, not because it was conceptually played out or over, but because it became, over time and as technology advanced, too easy to do, to make. The streamlining of the process of visual composition pulled it away from the writing, and made it design after the fact, and the after-the-fact-ness of the visual identity and arrangement of the text is exactly what concrete poetry denied. If we accept that visual manipulation of text is now a cultural norm, that both the process of doing it and the results aren’t particularly productive (in a subversive, discourse cracking kind of way), then one question we could ask is: Can we write a new, contemporary concrete poetry that functions not on visuality alone (form) but on production and reception as well? Can we begin processes of writing that will tear at the very discourse that produces those processes? What can we do, tied to these machines?

Once Buzz Spector and I were talking about concrete poetry, and he put forth the idea that concrete poetry had ended, not because it was conceptually played out or over, but because it became, over time and as technology advanced, too easy to do, to make. The streamlining of the process of visual composition pulled it away from the writing, and made it design after the fact, and the after-the-fact-ness of the visual identity and arrangement of the text is exactly what concrete poetry denied. If we accept that visual manipulation of text is now a cultural norm, that both the process of doing it and the results aren’t particularly productive (in a subversive, discourse cracking kind of way), then one question we could ask is: Can we write a new, contemporary concrete poetry that functions not on visuality alone (form) but on production and reception as well? Can we begin processes of writing that will tear at the very discourse that produces those processes? What can we do, tied to these machines?

The other day I began reading Darren Wershler(-Henry)’s The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting. I haven’t gotten very far yet, but it’s an interesting book, about the history of the typewriter and typewriting, about how our relationship with the machine has changed the way that we represent and think about writing, as well as the way that we actually write. Or wrote, because now we are in the midst of a related, yet new, discourse on writing and writing machines.One of the main reasons that I am interested in this book particularly (besides my general interest in Wershler’s work and these kinds of discursive histories more generally) is that typewriting provided me, many years ago, with the seeds of the idea for using processes that I now call hand-mechanical. A hand-mechanical process is any method that stands or slides between the rigidity of machine control and the variation of the human hand. I tend to think these techniques mostly in terms of printing and bookmaking, and indeed, print(mak)ing naturally carries these kind of soft, repetitive processes at its core. Some examples: setting lead type by hand, inking & wiping litho stones and etching plates, pulling sheets of paper from the vat, pulling a squeegee across a screen to force the ink through the stencil. All of these things, done over and over again, each time the same, each time a little different. The hand-mechanical is repetitive. Drawing and painting can be hand-mechanical as well. Drawing/painting through stencils, or with guides, or tape, or a pre-determined composition (Frank Stella, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, Eva Hesse, coloring books, paint by number, Andy Warhol). Knitting and crocheting are hand-mechanical, forming a larger structure through a network of small movements. The hand-mechanical tends toward compositions that are planned out beforehand.

Drawing and painting can be hand-mechanical as well. Drawing/painting through stencils, or with guides, or tape, or a pre-determined composition (Frank Stella, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, Eva Hesse, coloring books, paint by number, Andy Warhol). Knitting and crocheting are hand-mechanical, forming a larger structure through a network of small movements. The hand-mechanical tends toward compositions that are planned out beforehand. Writing is always somehow bound to the physical processes that enact it, and thus writing is always, to a degree, hand-mechanical. The very act of typing or writing out by hand the same 26 letters in different forms and combinations, according to pre-determined conventions (whether the author’s own or the culture’s) is a hand-mechanical activity. To write is to engage the hand, the body, with multiple technologies. When we are composing as we write (like I am now) the physicality of the activity moves to the background of our consciousness. When we are not composing, but still writing (like when we have to retype a handwritten document, or in the “uncreative writing” of Kenneth Goldsmith) the physicality of the activity becomes foregrounded, and we see ourselves as bound to the machine and the activity that it produces. The hand-mechanical occurs when a human being and a machine create as an assemblage, as a larger, creaking, organic and deliriously imperfect, machine.

Writing is always somehow bound to the physical processes that enact it, and thus writing is always, to a degree, hand-mechanical. The very act of typing or writing out by hand the same 26 letters in different forms and combinations, according to pre-determined conventions (whether the author’s own or the culture’s) is a hand-mechanical activity. To write is to engage the hand, the body, with multiple technologies. When we are composing as we write (like I am now) the physicality of the activity moves to the background of our consciousness. When we are not composing, but still writing (like when we have to retype a handwritten document, or in the “uncreative writing” of Kenneth Goldsmith) the physicality of the activity becomes foregrounded, and we see ourselves as bound to the machine and the activity that it produces. The hand-mechanical occurs when a human being and a machine create as an assemblage, as a larger, creaking, organic and deliriously imperfect, machine.  Almost everything we do, now, in a techno-logical society, is to a certain degree, hand-mechanical. As long as our activities are tied to the movement of our bodies, we are caught in the machine. Naming, locating, and outlining the hand-mechanical as an approach to creative practice will let us begin to see how that machine works.

Almost everything we do, now, in a techno-logical society, is to a certain degree, hand-mechanical. As long as our activities are tied to the movement of our bodies, we are caught in the machine. Naming, locating, and outlining the hand-mechanical as an approach to creative practice will let us begin to see how that machine works.

Yesterday afternoon my students were working on setting type for our class project. One of them had made the arrangement pictured above so that he didn’t have to hold on to the job stick while he was setting. Too perfect. The merging the of old and new media. Thanks to Peter Elliott for the innovation.

Yesterday afternoon my students were working on setting type for our class project. One of them had made the arrangement pictured above so that he didn’t have to hold on to the job stick while he was setting. Too perfect. The merging the of old and new media. Thanks to Peter Elliott for the innovation.

Hitting the road today so that I can be at the Pyramid Atlantic Book Arts Fair this weekend. I am an exhibitor at the fair, and this time I will have some books and broadsides from the Press at Colorado College as well as NewLights Press. It should be a good fair (and related events) some come on down if you're in the neighborhood. The Description:

Hitting the road today so that I can be at the Pyramid Atlantic Book Arts Fair this weekend. I am an exhibitor at the fair, and this time I will have some books and broadsides from the Press at Colorado College as well as NewLights Press. It should be a good fair (and related events) some come on down if you're in the neighborhood. The Description:

Pyramid Atlantic Art Center presents the 11th Biennial Book Arts Fair and Conference, the preeminent book arts event on the east coast. Now in its third decade, the fair will showcase a dynamic array of innovative book art, limited edition prints, fine papers, and specialty tools along with a rich program of notable speakers, demonstrations, and special exhibitions. This three day event will connect international artists, scholars, collectors, publishers, and art lovers. Serving to inform and inspire, the Book Arts Fair and Conference is a celebration of the printed form and the book as art.

The 2010 Pyramid Atlantic Book Arts Fair

Friday Nov. 5 - Sunday Nov. 7

Silver Spring Civic Building

Silver Spring, MD

Their website has a full schedule of times for the fair and other events.