skip to main |

skip to sidebar

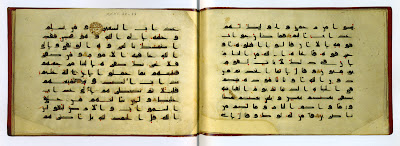

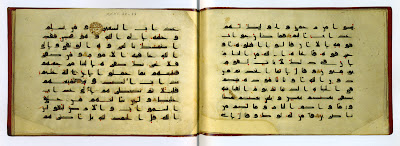

“A 9th-century Qur’an, Near East, in horizontal format, written on parchment in kufic script, with red dots for vowels and green dots indicating the glottal stop. The large gold roundel marks the end of a tenth verse.” Or. 1397, ff. 18v-19. [1]Speaking of the conventionality of written/printed language: one experience that can make the nature and limits of that conventionality immediately clear and palpable is the experience of a second language, an-other-language, especially if that language is rendered in a completely different alphabet.While working on the Al-Mutanabbi broadside project I got to learn a small amount of Arabic and the basics of how the written language works. It’s interesting how the “idea” can be the same (a phonetic language) but the implementation can be completely different. Completely different but still able to be comprehended and used. An-other technology.

“A 9th-century Qur’an, Near East, in horizontal format, written on parchment in kufic script, with red dots for vowels and green dots indicating the glottal stop. The large gold roundel marks the end of a tenth verse.” Or. 1397, ff. 18v-19. [1]Speaking of the conventionality of written/printed language: one experience that can make the nature and limits of that conventionality immediately clear and palpable is the experience of a second language, an-other-language, especially if that language is rendered in a completely different alphabet.While working on the Al-Mutanabbi broadside project I got to learn a small amount of Arabic and the basics of how the written language works. It’s interesting how the “idea” can be the same (a phonetic language) but the implementation can be completely different. Completely different but still able to be comprehended and used. An-other technology. “An 11th- or 12th- century Qur’an, from Iraq or Persia, written on paper in the Qarmatian style of eastern kufic script. The older system of red dots indicating vowels is combined with black vowel signs still in use today.” Or. 6573, ff. 210v-211. [2]The Arabic alphabet contains 29 letters, and each of those letters changes shape depending on where it falls in the word. Each character has a form for when it stands alone, when it begins a word, when it is in the middle of a word, and when it is at the end of a word. Like the “long s” that appears in old English, or the slight alterations that occur in English cursive letters to link them properly to the letter following them.

“An 11th- or 12th- century Qur’an, from Iraq or Persia, written on paper in the Qarmatian style of eastern kufic script. The older system of red dots indicating vowels is combined with black vowel signs still in use today.” Or. 6573, ff. 210v-211. [2]The Arabic alphabet contains 29 letters, and each of those letters changes shape depending on where it falls in the word. Each character has a form for when it stands alone, when it begins a word, when it is in the middle of a word, and when it is at the end of a word. Like the “long s” that appears in old English, or the slight alterations that occur in English cursive letters to link them properly to the letter following them. “Detail from the colophon page of volume three of Sultan Baybars’ Qur’an, 1305-6, with the signature of the master illuminator, Abu Bakr Sandal, inscribed in the ornamental semi-circles (right).” Add. 22408, f. 154v. [3]The Arabic alphabet reads right-to-left. Apparently, this is a huge “problem” for design programs (like Adobe InDesign) but not so much for word processing programs, like Microsoft Word. Or maybe not a problem for the software but for the user who has to buy a second version of InDesign in order to properly set Arabic. But one can hack one’s way through the Arabic in the left-to-right version of InDesign using the “Glyphs” palette, much like setting metal type out of a case. An-other language.

“Detail from the colophon page of volume three of Sultan Baybars’ Qur’an, 1305-6, with the signature of the master illuminator, Abu Bakr Sandal, inscribed in the ornamental semi-circles (right).” Add. 22408, f. 154v. [3]The Arabic alphabet reads right-to-left. Apparently, this is a huge “problem” for design programs (like Adobe InDesign) but not so much for word processing programs, like Microsoft Word. Or maybe not a problem for the software but for the user who has to buy a second version of InDesign in order to properly set Arabic. But one can hack one’s way through the Arabic in the left-to-right version of InDesign using the “Glyphs” palette, much like setting metal type out of a case. An-other language. “A 17th-century Qur’an from Persia written in nashki script, with an interlinear Persian translation in red nasta’liq script.” Or. 13371, ff. 313v-314. [4][…] [T]he Arabic language […] belongs to the Semitic family of scripts which includes among other Hebrew, Aramaic, and Syriac. A common feature of all these languages is the fact that their alphabets are composed almost entirely of consonants, vowel signs being added only later to facilitate reading. […] [5]

“A 17th-century Qur’an from Persia written in nashki script, with an interlinear Persian translation in red nasta’liq script.” Or. 13371, ff. 313v-314. [4][…] [T]he Arabic language […] belongs to the Semitic family of scripts which includes among other Hebrew, Aramaic, and Syriac. A common feature of all these languages is the fact that their alphabets are composed almost entirely of consonants, vowel signs being added only later to facilitate reading. […] [5] A detail of the previous image.It’s interesting to compare these manuscript Qur’ans to the European manuscript books, to see how they are similar and how they are different. How the rules of each culture (like the fact that illustration was forbidden in the Qur’an) helped to determine how the conventions of the written language developed. Paying attention to the conventions of various other languages can help us deconstruct our own, to pay attention to it, to dwell in it more fully, and to utilize it more incisively. 1. Colin F. Baker, Qur’an Manuscripts: Calligraphy, Illumination, Design, (London: The British Libray, 2007), 20-1. The numbers after each caption designate which manuscript and pages the images are from. All of the manuscripts are currently held at the British Library.2. Ibid., 24-5.3. Ibid., 46.4. Ibid., 78-9.5. Ibid., 13.

A detail of the previous image.It’s interesting to compare these manuscript Qur’ans to the European manuscript books, to see how they are similar and how they are different. How the rules of each culture (like the fact that illustration was forbidden in the Qur’an) helped to determine how the conventions of the written language developed. Paying attention to the conventions of various other languages can help us deconstruct our own, to pay attention to it, to dwell in it more fully, and to utilize it more incisively. 1. Colin F. Baker, Qur’an Manuscripts: Calligraphy, Illumination, Design, (London: The British Libray, 2007), 20-1. The numbers after each caption designate which manuscript and pages the images are from. All of the manuscripts are currently held at the British Library.2. Ibid., 24-5.3. Ibid., 46.4. Ibid., 78-9.5. Ibid., 13.

The first draft of this post started as a dull procession of facts about manuscript books—a natural danger, perhaps, of research based work. But the point of this is to generate new ideas. Here’s a not new idea that seems appropriate:“Production not reproduction.” [Phillip Zimmerman]How is scribal production (essentially the slow, embodied, re-production of a text) an act of production? Does the copying out of a text allow a reader to participate in it differently? Beyond copying and staying within the text, how does rendering it visually (incorporating images and “decorated” letters, designing/typesetting) and threading it through the structure of a book (a reproducible time-structure) change the way in which we read? Is the term “read” even appropriate anymore?The hand-mechanical activity of the scribe is devotional, meditative. But the content matters less (to me) than the action itself. It’s about understanding a text physically, bodily, experientially. Not moving through a building as a temporary occupant, but actively participating in its construction, living and working in it, becoming a shaper of space and time, of knowledge and experience.If possible (and it’s usually just a matter of time) I like to completely retype a text that I am working with (if I didn’t write it in the first place). Is this a waste of time? An obsessive habit? An invitation to “scribal error?” In my experience, the re-production of a text letter by letter allows me to understand it more thoroughly, more minutely, than “simply” reading. It’s like studying a text on an atomic level, like taking apart and rebuilding a machine in order to understand how it works. Hand typesetting provides the same kind of experience. It is a kind of reading that does not posit the text as before the reading, but a kind of reading that actively creates the text here and now, as an immanent, ongoing construction. Not eternal and unchanging, but experienced always in the present through constant change and repetition.

The first draft of this post started as a dull procession of facts about manuscript books—a natural danger, perhaps, of research based work. But the point of this is to generate new ideas. Here’s a not new idea that seems appropriate:“Production not reproduction.” [Phillip Zimmerman]How is scribal production (essentially the slow, embodied, re-production of a text) an act of production? Does the copying out of a text allow a reader to participate in it differently? Beyond copying and staying within the text, how does rendering it visually (incorporating images and “decorated” letters, designing/typesetting) and threading it through the structure of a book (a reproducible time-structure) change the way in which we read? Is the term “read” even appropriate anymore?The hand-mechanical activity of the scribe is devotional, meditative. But the content matters less (to me) than the action itself. It’s about understanding a text physically, bodily, experientially. Not moving through a building as a temporary occupant, but actively participating in its construction, living and working in it, becoming a shaper of space and time, of knowledge and experience.If possible (and it’s usually just a matter of time) I like to completely retype a text that I am working with (if I didn’t write it in the first place). Is this a waste of time? An obsessive habit? An invitation to “scribal error?” In my experience, the re-production of a text letter by letter allows me to understand it more thoroughly, more minutely, than “simply” reading. It’s like studying a text on an atomic level, like taking apart and rebuilding a machine in order to understand how it works. Hand typesetting provides the same kind of experience. It is a kind of reading that does not posit the text as before the reading, but a kind of reading that actively creates the text here and now, as an immanent, ongoing construction. Not eternal and unchanging, but experienced always in the present through constant change and repetition.

Mainly because I want to share all of the beautiful things I’ve been seeing. Last week I began doing some research on manuscript books. “Manuscript books” are books made entirely by hand. They are generally unique, usually (but not always) dating from the time before movable type, and are sometimes called “illuminated manuscripts.” The research up to this point has been general at best, just a few simple, well-illustrated books about medieval European books and early Qu’rans, just to provide a broad story and sample of what exists. But already they are pointing to new directions.

Mainly because I want to share all of the beautiful things I’ve been seeing. Last week I began doing some research on manuscript books. “Manuscript books” are books made entirely by hand. They are generally unique, usually (but not always) dating from the time before movable type, and are sometimes called “illuminated manuscripts.” The research up to this point has been general at best, just a few simple, well-illustrated books about medieval European books and early Qu’rans, just to provide a broad story and sample of what exists. But already they are pointing to new directions.Modern printed books attempt to convey some of the rhythms and emphasis of speech by a whole series of typographical conventions, including indented paragraphs, spaces between sentences, capital letters, italics, and a large repertoire of punctuation marks […]. Medieval punctuation was haphazard at best. Mostly, scribes made use of what we now call decoration. A big initial marks a major opening or division of the text. A slightly smaller initial may indicate a chapter or a paragraph of somewhat lesser significance. A small illuminated initial marks a break in the text less weighty than a larger initial but more important than a simple capital letter.

The hierarchy depended not on any standard size as such but on the scale of any initial in relation to another in the same manuscript. […] Once the relative hierarchy is put in context […] we have a whole new tool for interpreting medieval texts. In that sense, decoration is a device for reading a text as sophisticated as punctuation is today. […] [1]

[emphasis added]

I would add to that series of “typographical conventions” the spacing between individual words and standardized spelling. The conventional nature of written and printed language is important for two reasons: 1) These conventions developed over time in many different circumstances, conditioned by different languages, technologies, cultures, economies, etc. and that points to the fact that our “laws” of grammar, usage, definitions, and spellings are not natural truths that accurately represent a pure language. 2) These conventions that we have internalized play a major role in that way that we read, in the way that we experience written and printed language. Reading as a practice has changed over time, and it continues to change, especially now, as we stand in the chaos of another transformation of the technology of writing. And thus it is possible to imagine and construct new ways of reading, new legibilities of text, by interrogating the conventional nature of written and printed language. This is certainly not a new idea, but it’s one that seems particularly critical now, again. The space of our new technologies of reading and writing has opened up new avenues of contestation. The only thing at stake is meaning. These old books were made during a period of massive flux and expansion, and looking at them closely might yield new ways for us to participate in our own astonishing flux.So I am imagining these posts (theoretically confined to this week but probably continuing anyway) as looking closely at different examples from manuscript books and breaking them down visually/functionally, hopefully generating some ideas in the process. As always, we’ll see what happens, where we end up.

1. Christopher de Hamel, The British Library Guide to Manuscript Illumination: History and Techniques, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 21-4. The image at the start of this post was taken from that same book (p. 46) and is from a “tenth-century English manuscript of the works of St. Aldhelm.”

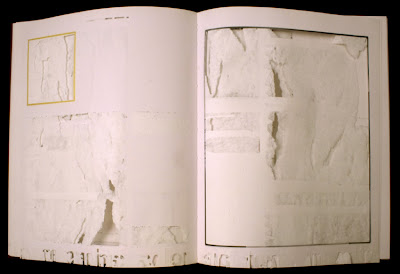

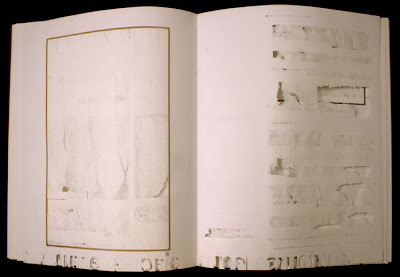

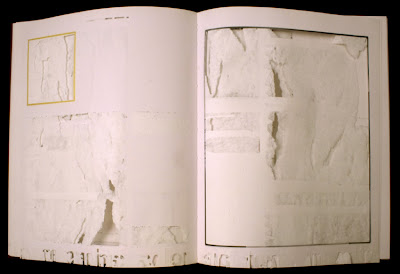

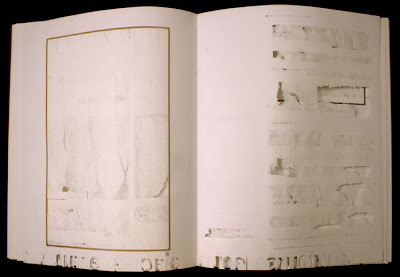

[Note: I noticed yesterday when I was looking at the other altered books on this blog that I had not “officially” posted this book as complete. So here it is. It was actually finished at the beginning of February, 2011.]

Altered book by NewLights Press: Aaron Cohick, et al.

220 pages, hardcover, casebound, 11” x 18” (open)

Mass produced art history book altered through delamination

Unique

2011

Purchased for a private collection.

The original book was:

Brandon Taylor, Collage: The Making of Modern Art, (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004). It is one of the best surveys of collage in modern & postmodern art that I have read.

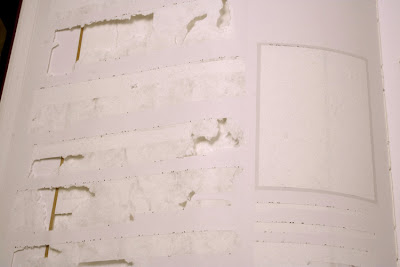

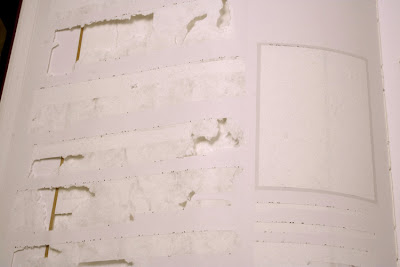

The last image shows a detail of the text that was runs in a continuous line along the bottom of the book. It was written subtractively (by removing words) from the original text. But you, lucky you, can read the full text below:

The method of constructing from parts. It is the synthesis of colourless, white or grey-black areas of colour, or the arrangement of unexpected proportions. Written in the graphics of a powerful weapon aware of the very different demands of concluding that the system of montage is dialectic. It is a statement, after all, that neither Klutsis or Lissitzky could have made; nor Heartfield or Hoch, “Lyricism is the crown of life: Constructivism is its already existing soft-porn surfaces, even, on occasion, a castrating machine. Yet the most persistent motif is one that only collage as a device could generate: the softness of parts not only indexically presented but eroticized as a purely photographic contrast of textures: grass, gravel or wood, inside barbed-wire, in the midst of dry leaves, or, in one case, inverted on the body and placed against the austere brick superstructure.

Such works not attempted hitherto: the minutest visible variations in photographic color and tone, magnified by the tell-tale curves of the paper’s scissored edges. By systematically excising one and placing it against a subtly contrastive one, an interval, a gap, which is in itself stimulating. ‘It is sight’, he had suggested, proposing desublimation of the senses: ‘The optical environment in which ‘the development of a bland, large, balanced, Apollonian art…in which an intense detachment this detachment that enabled him to see a Cubist collage by Picasso or Braque in a radically anti-illusionistic way: ‘the Cubists always emphasized the identity of the picture as a flat and more or less abstract pattern rather than a representation’. To choose between them is preferable to ambiguity: collage had now attained to the full and declared three-dimensionality we automatically attribute to the notion “object”, and was being transformed, in the course of a strictly coherent process with a logic all its own, into a new kind of houses we live in and furniture we use’. rectangles littered with small pictures rectangles are references to technology, the industrial process, heavy machinery. Thirdly, as a physical object it occupies a kind of middle ground between the single, exhibitable object and the flickering succession of a moving film. Turning its pages is a one-person affair, addressed to relatively private experience as opposed to the collectivity of a show. Yet politics was never far away. To that extent it may be mourning the flowering of quiet defiance: she knew such works could not be exhibited. But she was increasingly vulnerable. She was being watched and possibly denounced, she managed to escape attention.

text written in opposition to works of ‘degenerate’ modernism is positioned close by. The art historian T. J. Clark has studied the problem: the work to annihilate the negation of the negation’. she boldly mangled several works to produce collage of her own. The background to this benevolent act of ‘completion’ is inevitably complicated by Krasner’s relationship to Pollock. ‘”Waste not, want not”, open it out and let space back in, it turns out that Krasner had her own adventure tumbling, thinking that Krasner soon became disenchanted with the work.

My studio was hung with a series of black and white drawings I had done. I hated them and started to pull them off the wall and tear them and throw them on the floor…. Then another morning began picking up torn pieces of my drawings and re-glueing them. Then I started. I got something going I started. People would just come and wouldn’t put on a show or entertain. They came happily and sat down and left four hours later: you’d listen to some music and you’d look at things. What I enjoyed was not the conversation but the things we looked at…there were evenings where there was not much talk.

Altered book by NewLights Press: Aaron Cohick, et al.

220 pages, hardcover, casebound, 11” x 18” (open)

Mass produced art history book altered through delamination

Unique

2011

Purchased for a private collection.

The original book was:

Brandon Taylor, Collage: The Making of Modern Art, (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004). It is one of the best surveys of collage in modern & postmodern art that I have read.

The last image shows a detail of the text that was runs in a continuous line along the bottom of the book. It was written subtractively (by removing words) from the original text. But you, lucky you, can read the full text below:

The method of constructing from parts. It is the synthesis of colourless, white or grey-black areas of colour, or the arrangement of unexpected proportions. Written in the graphics of a powerful weapon aware of the very different demands of concluding that the system of montage is dialectic. It is a statement, after all, that neither Klutsis or Lissitzky could have made; nor Heartfield or Hoch, “Lyricism is the crown of life: Constructivism is its already existing soft-porn surfaces, even, on occasion, a castrating machine. Yet the most persistent motif is one that only collage as a device could generate: the softness of parts not only indexically presented but eroticized as a purely photographic contrast of textures: grass, gravel or wood, inside barbed-wire, in the midst of dry leaves, or, in one case, inverted on the body and placed against the austere brick superstructure.

Such works not attempted hitherto: the minutest visible variations in photographic color and tone, magnified by the tell-tale curves of the paper’s scissored edges. By systematically excising one and placing it against a subtly contrastive one, an interval, a gap, which is in itself stimulating. ‘It is sight’, he had suggested, proposing desublimation of the senses: ‘The optical environment in which ‘the development of a bland, large, balanced, Apollonian art…in which an intense detachment this detachment that enabled him to see a Cubist collage by Picasso or Braque in a radically anti-illusionistic way: ‘the Cubists always emphasized the identity of the picture as a flat and more or less abstract pattern rather than a representation’. To choose between them is preferable to ambiguity: collage had now attained to the full and declared three-dimensionality we automatically attribute to the notion “object”, and was being transformed, in the course of a strictly coherent process with a logic all its own, into a new kind of houses we live in and furniture we use’. rectangles littered with small pictures rectangles are references to technology, the industrial process, heavy machinery. Thirdly, as a physical object it occupies a kind of middle ground between the single, exhibitable object and the flickering succession of a moving film. Turning its pages is a one-person affair, addressed to relatively private experience as opposed to the collectivity of a show. Yet politics was never far away. To that extent it may be mourning the flowering of quiet defiance: she knew such works could not be exhibited. But she was increasingly vulnerable. She was being watched and possibly denounced, she managed to escape attention.

text written in opposition to works of ‘degenerate’ modernism is positioned close by. The art historian T. J. Clark has studied the problem: the work to annihilate the negation of the negation’. she boldly mangled several works to produce collage of her own. The background to this benevolent act of ‘completion’ is inevitably complicated by Krasner’s relationship to Pollock. ‘”Waste not, want not”, open it out and let space back in, it turns out that Krasner had her own adventure tumbling, thinking that Krasner soon became disenchanted with the work.

My studio was hung with a series of black and white drawings I had done. I hated them and started to pull them off the wall and tear them and throw them on the floor…. Then another morning began picking up torn pieces of my drawings and re-glueing them. Then I started. I got something going I started. People would just come and wouldn’t put on a show or entertain. They came happily and sat down and left four hours later: you’d listen to some music and you’d look at things. What I enjoyed was not the conversation but the things we looked at…there were evenings where there was not much talk.

Fig. 06.11.01

Fig. 06.11.01

A scriptorium. The imaginary space of this construction. [1]These past two weeks I’ve been finishing another volley of the NewLights broadsides, spending many hours a day cutting and peeling the negative space of text away from the text itself. The process creates its own tracks, is multiply inscriptive, multiply legible. And because of that activity, I have been thinking a lot about “the body writing,” and I have been about thinking the broadsides and the altered books in relation to scribal activity and manuscript books. No conclusions yet, of course. But somewhere I see the slow pulse of a poetics of inscription, of printing, of making. Not a poetics about, but of.[…] writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing. […] [2]

Barthes uses the term “scriptor” to describe his “modern” author or writer. That particular term is very unstable, especially when examined in relationship to the activity of the scribe, typesetter, and/or printer. Is there a point where “authorship” ends, and “scripting” begins? Is it the point “where all identity is lost, starting with the identity of the body writing”?So we will start with this term “scriptor,” and begin to map out the space it occupies, or creates…scribe n. 1. historical a person who copied out documents. informal, often humorous a writer; especially a journalist. 2. Jewish History an ancient Jewish record-keeper or, later, a professional theologian and jurist. 3. (also scriber or scribe awl) a pointed instrument used for making marks to guide a saw or in signwriting. v. 1. chiefly poetic/literary write. 2. mark with a pointed instrument.

script n. 1. handwriting as distinct from print; written characters. writing using a particular alphabet: Russian script. 2. the written text of a play, film, or broadcast. 3. Brit. a candidate’s written answers in an examination. 4. Computing a program or sequence of instructions that is carried out by another program rather than by the computer processor. v. write a script for.

scriptorium n. chiefly historical a room set apart for writing, especially one in a monastery where manuscripts were copied. [3]

[…] the modern scriptor is born simultaneously with the text, is in no way equipped with a being preceding or exceeding the writing, is not the subject with the book as predicate; there is no other time than that of the enunciation and every text is eternally written here and now. The fact is (or, it follows) that writing can no longer designate an operation of recording, notation, representation, ‘depiction’ (as the Classics would say); rather, it designates exactly what linguists, referring to Oxford philosophy, call a performative, a rare verbal form (exclusively given in the first person and in the present tense) in which the enunciation has no other content (contains no other proposition) than the act by which it is uttered—something like the I declare of kings or the I sing of very ancient poets. […] For [the modern scriptor] […] the hand, cut off from any voice, borne by a pure gesture of inscription (and not of expression), traces a field without origin—or which, at least, has no other origin than language itself, language which ceaselessly calls into question all origins. […] [4]

Fig. 06.11.02

Fig. 06.11.02

Marking/making the word & the book is a game with serious consequences. "The Cathedral of Fulda preserves an early theological manuscript whose wooden covers are reputedly scored with the marks of sword blows received when St. Boniface, a German evangelist in the eighth century, used the book as a shield to ward off a pagan attack. The book was none too effective in this respect, and Boniface was killed, but the book has been held as a treasured relic ever since." [5] The imaginary space of this construction.1. Image from: Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, (Boston: Nonpareil Books, 1980), 4.2. Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” Image — Music — Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 142.3. Definitions are from the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Revised Tenth Edition, 2002.4. Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” Image — Music — Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 145-6.5. Image and description from: David Pearson, Books As History: The importance of books beyond their texts, (London: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2008), 132-3.

Here on a rainy morning and there is, as usual, too much interesting stuff to read on the Internet. Here on a rainy morning and that old feeling of not knowing what I am going to write. (Terrifying? Exhilirating? Dull and senseless? All of these?) I was just reading the latest installment of the HTMLGiant series “What Is Experimental Literature? {Five Questions}” (The latest post, as of the time of this writing, was with Eileen Myles.) Often in the answers to the questions there is some discussion of the label “experimental literature.” Eileen Myles seems the most suspicious of this term, saying that she “feel[s] like [she] is being asked to endorse a brand.”And this discussion makes me wonder about that description of this press, up and over there in the sidebar --------------------------------------->& I am always wondering about the “description” of what this “press” “does.”Right now I am actually more concerned with the “literature” than I am with the “experimental.”“Everything that was literature has fallen away from me.”The reason that I call the term “literature” into question for use over there is because it connotes a finished and definable product, a thing, done, called “literature.” And there are of course a host of cultural qualifications that come along with that term. But emphasis on product is not really the whole point of what NewLights is up to. We make things, yes, but those things are dynamic, (hopefully) enacting processes in and outside of themselves.So what do we use instead of “literature?” How about “writing?” That helps to transfer the emphasis to process. And maybe the “experimental” will be enough to say “writing not like writing.” Things, made & making.Perhaps I will change the description tomorrow, but tomorrow how knows what will change?

[UPDATE: The word was changed to "writing" on 06/23/11.]

The other day I received an email announcement from Mud Luscious Press, which is run by newly anointed NewLights author J. A. Tyler. The announcement was for the new book in their Nephew chapbook series, Meat Is All, by Andrew Borgstrom. It caught my attention for a few reasons: 1) the cover, shown above, looks great, 2) the excerpt available is weird & interesting, and 3) the edition, or the mode of production-distribution of it, was described as: “This book will be available for 90 days or until 150 copies are sold, whichever comes first.”I was intrigued by this idea, so I wrote to Mr. Tyler asking him to explain a bit more. Here’s his response:

The other day I received an email announcement from Mud Luscious Press, which is run by newly anointed NewLights author J. A. Tyler. The announcement was for the new book in their Nephew chapbook series, Meat Is All, by Andrew Borgstrom. It caught my attention for a few reasons: 1) the cover, shown above, looks great, 2) the excerpt available is weird & interesting, and 3) the edition, or the mode of production-distribution of it, was described as: “This book will be available for 90 days or until 150 copies are sold, whichever comes first.”I was intrigued by this idea, so I wrote to Mr. Tyler asking him to explain a bit more. Here’s his response:We take orders for our Nephew titles for either 90 days (max.) or for 150 copies (max.) and we don't print the book until we have reached one of those two points. This allows us to guarantee that we only print exactly as many copies as are ordered (zero waste, more effective production cost structures) and it also allows us to guarantee buyers that even if a title doesn't sell out immediately, they will be waiting a maximum of 90 days to receive their books (not a bad wait time for a pre-order of an exclusive title).

Then I asked him how they were actually making these books, and he said:Our printing is done by our regular Mud Luscious Press printer, facilitated by David McNamara at Sunnyoutside - this printer allows us to do runs as small as 25 copies and as large as we like (David is fantastic!).

That’s a damn smart & practical way to handle the production of a book. And the idea of a time-based edition could yield other interesting results. Speculation aside, this approach is a concrete example of the way that new printing technologies (print-on-demand, digital presses capable of quality printing and short runs) and new distribution the technologies (the Internet) are changing the ways that small press books are produced. This kind of approach would not have been possible (at least in this streamlined of a form) 10 years ago. These kinds of innovations and changes are extremely important. And it helps to reinforce my conviction that this is the most exciting time to be engaged in textual culture since Gutenberg made that crazy invention of his.

The following quote is from: Richard Sennett, The Culture of the New Capitalism, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006) 58-9. It offers a sociological/cultural definition of authority, which is perhaps useful for our examination of authorship:[…] Authority names a complex social process of dependency. A person possessed of authority differs from a tyrant, who deploys brute force to be obeyed. As Weber long ago observed, someone possessed of authority elicits voluntary obedience; his or her subjects believe in him. They may believe him to be harsh, cruel, unjust, but still, something more is present. People below come to rely on those above them. In charismatic forms of authority, those below believe that the authority figure will complete and enable what is incomplete and disabled in themselves; in bureaucratic forms of authority, they believe that institutions will take responsibility for them. […]

What’s interesting about this definition is that it points out the fact that people desire authority—it “elicits voluntary obedience.” We, as readers, expect and believe that we need the author(ity) to explain & guarantee the meaning/value of the work. Cutting away the author is to free the work from its primary signifier. Without this we are alone, tentative, fumbling. There is anxiety. There does not seem to be a goal.I do not ask authority or authorship from the mug that I’m drinking coffee out of. Its specific function frees me of that anxiety. Can “use value” replace the author(ity) in art?

The goal is no longer to be an “artist” or “author:”

The goal is no longer to be an “artist” or “author:”[…] The new mode of book production […] In the figure of the master printer, […] produced a “new man” who was adept in handling machines and marketing products even while editing texts, founding learned societies, promoting artists and authors, advancing new forms of data collection, and contributing to erudite disciplines. […] [1]

But the “master printer” should be dissolved into the press itself:[…] The new mode of book production […] In the figure of the small press, […] produced a “new productivity” that was adept in handling machines and marketing products even while editing texts, founding learned societies, promoting artists and authors, advancing new forms of data collection, and contributing to erudite disciplines. […]

The emphasis, obviously, remains on production, but what an expanded list of activities, all out there in the world.1. Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 154. The image in this post was scanned from the cover of the book. The caption describing it reads: “A printer’s shop, detail of an engraving from Nova Reperta, a series of prints, designed by Vasari’s pupil, Stradanus, in the 1580s, engraved and published by the Antwerp firm of Galleus. […]”

HTMLGiant is running a series by contributor Christopher Higgs called "What is Experimental Literature?" The posts are essentially mini-interviews with a different writer each time, gathering various thoughts on, you guessed it, "experimental fiction." This week's post featured NewLights author Brian Evenson, and it is a really interesting read. My favorite jewel-like gem is:[...] That strikes me as the heart of innovative writing: necessity and seriousness (even if it’s a comedic seriousness) inextricably bound to a real attention to language and form, whatever the specifics of that attention might be. All the other things that we might find in innovative writing–typographical experimentation, sexual transgressiveness, narrative disruption, verbal bedazzlement, etc., etc.,–all of which are readily identifiable and can be very good things in the right hands, they all come secondary to that. But since those things are much easier to talk about, we tend to think of them as characterizing innovative writing. But such characterizations are faulty, maybe even lazy, and I think end up missing the point. [...]

You can read the rest here.Also, Brian has a related essay in this month's issue of The Collagist, which is also really good, and deals with an idea (the process/aesthetics of stripping away) that I am very, very interested in.

When I was first thinking about and planning this series of posts, the idea was to base them on a close reading of two essays, the classics on the subject: “The Death of the Author” by Roland Barthes, and “What is an Author?” by Michel Foucault.B O R I N G!Actually, no, not boring, not at all. But if the intent here is to look critically at authorship now, then staying within just those two (authoritative) essays doesn’t make much sense. Refined approach: use the reading of the essays as a structuring principle, but build the “text” from in situ writing and other sources. Keep the authorial on its guard, and do not be beholden to just two powerful voices, no matter how insightful they are, no matter how much you may want to agree with them.& keep up the interchange of this series on authorship with the other series on The Hand-Mechanical and The Democratic Multiple. The switching between the three is the movement of this practice.& a new book this weekend, related & humane, and bringing other things back around. From Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 37-8:The modern era is often described as a skills economy, but what exactly is a skill? The generic answer is that skill is a trained practice. In this, skill contrasts to the coup de foudre, the sudden inspiration. The lure of inspiration lies in part in the conviction that raw talent can take the place of training. Musical prodigies are often cited to support this conviction—and wrongly so. An infant musical prodigy like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart did indeed harbor the capacity to remember large swatches of notes, but from ages five to seven Mozart learned how to train his great innate musical memory when he improvised at the keyboard. He evolved methods for seeming to produce music spontaneously. The music he later wrote down again seems spontaneous because he wrote directly on the page with relatively few corrections, but Mozart’s letters show that he went over his scores again and again in his mind before setting them in ink.

We should be suspicious of claims for innate, untrained talent. “I could write a good novel if only I had the time” or “if only I could pull myself together” is usually a narcissist’s fantasy. Going over an action again and again, by contrast, enables self-criticism. Modern education fears repetitive learning as mind-numbing. Afraid of boring children, avid to present ever-different stimulation, the enlightened teacher may avoid routine—but thus deprives children of the experience of studying their own ingrained practice and modulating it from within.

Skill development depends on how repetition is organized. This is why in music, as in sports, the length of a practice session must be carefully judged: the number of times one repeats a piece can be no more than the individual’s attention span at a given stage. As skill expands, the capacity to sustain repetition increases. In music this is the so-called Isaac Stern rule, the great violinist declaring that the better your technique, the longer you can rehearse without becoming bored. There are “Eureka!” moments that turn the lock in a practice that has jammed, but they are embedded in routine.

The clip above is from Emile de Antonio's 1972 film Painters Painting. The film itself (highly recommended, by the way) is made up of interviews with artists, collectors, critics, and dealers. This clip shows part of the interview with Andy Warhol. Note how he's also holding a microphone, as if he's conducting the interview as well. Warhol's "film crew" can also be seen in the background/mirror.

“A 9th-century Qur’an, Near East, in horizontal format, written on parchment in kufic script, with red dots for vowels and green dots indicating the glottal stop. The large gold roundel marks the end of a tenth verse.” Or. 1397, ff. 18v-19. [1]

“A 9th-century Qur’an, Near East, in horizontal format, written on parchment in kufic script, with red dots for vowels and green dots indicating the glottal stop. The large gold roundel marks the end of a tenth verse.” Or. 1397, ff. 18v-19. [1] “An 11th- or 12th- century Qur’an, from Iraq or Persia, written on paper in the Qarmatian style of eastern kufic script. The older system of red dots indicating vowels is combined with black vowel signs still in use today.” Or. 6573, ff. 210v-211. [2]

“An 11th- or 12th- century Qur’an, from Iraq or Persia, written on paper in the Qarmatian style of eastern kufic script. The older system of red dots indicating vowels is combined with black vowel signs still in use today.” Or. 6573, ff. 210v-211. [2] “Detail from the colophon page of volume three of Sultan Baybars’ Qur’an, 1305-6, with the signature of the master illuminator, Abu Bakr Sandal, inscribed in the ornamental semi-circles (right).” Add. 22408, f. 154v. [3]

“Detail from the colophon page of volume three of Sultan Baybars’ Qur’an, 1305-6, with the signature of the master illuminator, Abu Bakr Sandal, inscribed in the ornamental semi-circles (right).” Add. 22408, f. 154v. [3] “A 17th-century Qur’an from Persia written in nashki script, with an interlinear Persian translation in red nasta’liq script.” Or. 13371, ff. 313v-314. [4]

“A 17th-century Qur’an from Persia written in nashki script, with an interlinear Persian translation in red nasta’liq script.” Or. 13371, ff. 313v-314. [4] A detail of the previous image.

A detail of the previous image.